Debate: Optimal management for unruptured brain aneurysms

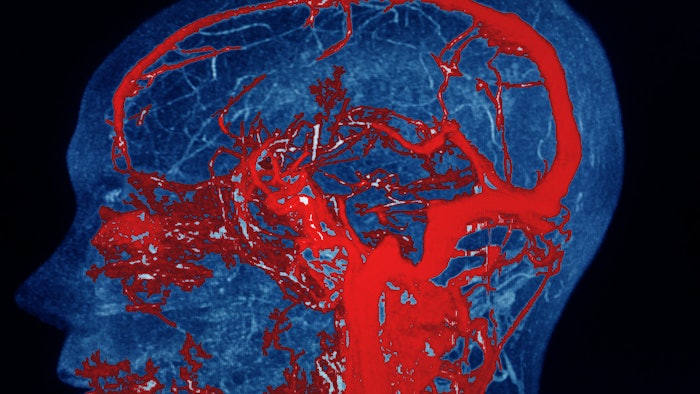

Unruptured brain aneurysms have become a clinical conundrum. Once rare because there are few to no visible signs or symptoms, growing and significant numbers of unruptured aneurysms are being discovered incidental to imaging performed for other reasons. There are no consistent guidelines for management, and there is no clear consensus on how to approach treatment, surveillance or referral.

“We all know what to do when an aneurysm ruptures, but the decision about who cares for patients with an unruptured aneurysm and how they manage it depends very much on where you practice,” said Joanna Schaafsma, MD, PhD, assistant professor of medicine at the University of Toronto in Canada. “Where I trained in the Netherlands, it is more common for neurologists to manage unruptured aneurysms; then I moved to Canada where neurology management is uncommon.”

Schaafsma will take one side of a special debate on “The Unruptured Aneurysm – Follow, Treat, Refer?” on Thursday, March 18, from 9:15-10:15 a.m. CDT. She was asked to argue that there is no need for all aneurysms to be referred to or treated by a neurosurgeon or neurointerventionalist; neurologists are well trained to follow patients and refer for treatment as needed.

Stavropoula I. Tjoumakaris, MD, professor of neurosurgery at Jefferson Medical College in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, will take the opposing position. She will argue all aneurysms should be referred to a neurosurgeon or neurointerventionalist for management; they are best equipped to evaluate patients and decide whether to treat or to follow.

The clinical reality, Schaafsma said, is the majority of aneurysms do not rupture and therefore, most patients would not need aneurysm repair. The most practical approach for patients who do not need such intervention is long-term follow-up and referral for treatment if and when imaging shows signs of possible progression toward rupture.

“Most arguments for and against intervention for unruptured brain aneurysms are based on clinical features of the patient, the size or location of the aneurysm, factors the neurologist can determine and evaluate,” she said. “The technical aspects of treatment, the areas where neurosurgeons and neurointerventionalists are expert, are a smaller part of the decision.”

The key complication in management decisions in these patients is the need to compare the long-term risks of rupture versus the immediate risks of intervention, Schaafsma said.

Although it is difficult to accurately assess relative risks on such vastly different time scales, the evidence suggests 5-year rupture risk associated with surveillance and the acute risks associated with intervention are both similar and small in the majority of patients, typically less than 5% regardless of the management choice.

“The decision-making isn’t easy because the consequences of both choices can be devastating to the patient,” she said. “And while subarachnoid hemorrhage is more rare than stroke, it tends to occur in younger patients than stroke and accounts for a loss of productive life years similar to that of ischemic stroke. In reality, I advocate for multidisciplinary decision-making to conclude on the most optimal strategy. This debate will give attendees tools that will make it easier to make those management decisions.”